An early version of this was posted to my Autos and Economics blog in August 2013.

Economics helps explain disarray in politics, at least politics US-style. Put every voter on a line, from right to left; candidates move towards the center. With a little bit of detail added, this model, due to Hotelling, helps clarify the strategic nature of our electoral game. (Harold Hotelling’s simple model of product differentiation dates to 1929. The politics version is the median voter theory.)

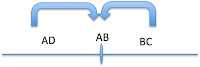

Where on a small beach would two pushcart vendors locate? Assume they start on the ends of the beach, each to their own side. They then split the business – everyone goes to the nearest vendor, with the person in the very middle indifferent which he chooses. But let one vendor push his cart partway towards the center, and that cart then splits the business that lies between, plus everything towards their end, and so gets more than half the business. The response is obvious: the other cart moves towards the center as well. Repeat, and eventually they’re next to each other, at the center of the beach.

So let’s look at an election to Congress. That process starts with primaries; there’s lots of local variation, but for simplicity assume they’re limited to party members. Now voting is inconvenient, and primaries don’t always get much publicity. So let’s further assume that only those who really care vote. Candidates align themselves at the center of their party, and so we get one candidate at the 1/4 mark, another at the 3/4 mark. He who can move most successfully to the center wins the popular vote. If one candidate missteps and does not quite move to the center, the other candidate can take advantage of that. Of course random factors matter – an untimely scandal, spending money unwisely, misjudging which states are on the edge and so not allocating enough time, or even personality. The model doesn’t capture everything.

This simple model highlights the dilemma Republicans (and in some races, Democrats) face, as the primary system pulls them to the right, with the issue of race (plus, less centrally, social nostrums) uniting a large enough block of activists to turn out to vote. As activists moved further from the center, that suggested that Democrats could win presidential elections even with weak candidates, by moving to right of center. Put in a strong candidate, a good campaigner such as a Clinton or an Obama, and you have a landslide. (Strong candidates and strong presidents aren’t the same thing – we elect people because they’re good at campaigning, not at policy or administration or negotiating with Congress.) Party activists who love the game, or love power are happy with this process. However, the party faithful will typically be unhappy with their final candidate, because the median activist isn’t a centrist.

Now lots of assumptions are hidden in this model. However, we don’t need a perfectly uniform distribution, or (with lots of caveats) only one dimension. We can, for example, let money sway matters, allowing candidates to “buy” votes. Of course two can play that game, and if it’s harder to buy votes the further you are from a potential voter’s position, then there’s still pressure to move towards the other candidate.

However, the model does require flexibility; voters opt for whomever is closest to them, even if they’re at one end of the spectrum and the candidate is all the way in the center. In other words, no one running for office gets locked into their initial positions. (In industrial organization, the Stackelberg model assumes that’s not the case. We however did not go through that duopoly model this term.) A second crucial assumption is that there are only two players; three’s a crowd, and there’s no equilibrium strategy. Third, if the market is a circle rather than a line, then two players move as far apart as they can, the opposite result – but in my judgment that’s not how politics works, even if the extreme right and the extreme left may be hard to distinguish on strong state issues (think Weimar Germany, where both the right and the left were nascent dictators and central planners).

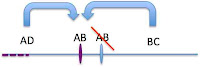

So why are our politics not centrist? First, there seems to be a limit on how quickly (that is, how far) a candidate can re-center after the primary. In terms of the Hotelling model, if voters are limited in how far they will travel – they won’t vote for someone who “betrays” them – then candidates will be limited in how far they can reposition themselves after the primary election. (In the Hotelling model, this comes for example from using the square of the distance a voter must travel.) The harder it is for a Republican to shift away from positions needed to win a primary, the easier it is for the Democrats. But potentially the Democrats enter the race with similarly untenable positions, if their primaries are dominated by activists far from the political center. Casual empiricism, though, suggests that while there is a distinct “Right” in American politics, there is no Left – the US has never had a strong Socialist Party, or even a Labor Party. What “liberal” means is unclear. And that’s an important point. Due to their diffuse positions those with some sort of liberal inclination have only a weak pull on a candidate, and a good grassroots campaign can turn out their vote.

[Actually, in the US there is to my knowledge no far right party. However, there are small Communist, Socialist and Green parties. That’s good news for the Democrats, most of the time, because that means that there’s not much Left left within the party (however strident claims to the contrary of the Right might be). That makes the Democrats more centrist from the git-go, as rival parties mean that the extreme within the Democratic party isn’t very extreme. In contrast, the Tea Party is a loose caucus, not a party, and doesn’t try to run candidates under a 3rd party banner in primaries. So if I try to incorporate that explicitly in the model the Democratic Party primary victor will be more centrist, whereas the “Tea Caucus” activism results in a primary victor to the right of center even within the Republican Party.]

In the last election, Republican candidates did not move. Perhaps this was a defect in the candidates themselves, or in their use of the same political advisors they employed in the primary, who were unable to distance themselves from their “natural” constituency. However, it’s not just been this one election, and the Democrats (rhetoric aside) seem to be center or center-right. The odd election when a third-party candidate has traction helps bolster this argument, as they then pull a block of voters who might otherwise be convinced to hold their nose and vote for a candidate too centrist for their tastes. The result is electoral disaster for one or the other party, as happened to the Democrats when Ralph Nader nibbled away at the more liberal part of their base.

Of course if being an incumbent get’s you close to half the vote, then strategy doesn’t much matter – an incumbent has to try hard to lose. Redistricting sometimes throws open the process. At least on the margins scandals can matter. In addition, for the House (but not the Senate) local issues can have salience. In practice, though, that seems to mean that rural candidates are always pro-farmer, whatever their party label. In other words, on local issues competent candidates of all stripes move so far to the center as to be indistinguishable. In any case, to the extent that incumbency dominates other factors, the only elections where this Hotelling model matters are ones for open seats – whether one views Romney’s candidacy as amusing or as sad, if incumbency really matters, it was doomed all along to irrelevance.

To sum up, the Hotelling model suggests that a large swath of voters will always be unhappy with presidential candidates, come the general election. Our politicians are “slick” and “untrustworthy,” flip-flopping, betraying those who worked for them in the primaries. Thanks to smaller electoral districts and hence a less diverse electorate – gerrymandering accentuates that – members of the House will also be more polar than the electorate as a whole. Granted, you always want to bargain down to the wire. But if the center dominates, then you do end up with a deal. That doesn’t seem to be happening today, and this simple economic model suggests that all that is required to generate this is the rise of a modest-sized “sticky” right.

Addendum: Economics insists that models aren’t sensible if they don’t lead to equilibrium behavior. A “sticky” right opens room on the left for a third-party candidate, because it leads Democrats to move to the right of center. If political entrepreneurs succeed in finding issues that will unify those to the left, then the center can lose all salience. Now the right end of the US spectrum seems to have defined itself around racial and class lines, white and prosperous, with a largely overlapping group of social conservatives. That’s a shrinking base, but the Hotelling model suggests that as long as we maintain a system of party-oriented primaries, that base won’t become irrelevant anytime soon, at least for the House of Representatives. This is not what many political pundits assume to be the case, but does match the continued power of a distinct minority in the House. We’ll see come fall whether the Senate continues to be less affected.

One other implication is that in districts with strong incumbents, it’s hard to motivate the average person who might vote for an opposition candidate. Only strongly driven voters participate – in other words, you get kooky candidates, who take positions incompatible with any sort of move to the center. That reinforces the strength of the incumbent…